Update: splatr has a Website!!

I built a paint program. In 2026. On purpose.

Not because the world desperately needed another image editor, but because I wanted a simple bitmap editor on my Mac that didn’t make me feel like I was committing some kind of cardinal sin against my hardware.

The Problem

Here’s the thing: macOS doesn’t ship with a basic paint program (well, it used to until OS X came around…RIP MacPaint). Preview can annotate. Photos can adjust. But if you want to just draw something to mess around with- some pixels on a canvas—your options are surprisingly grim.

You can use an Electron app that bundles an entire Chromium instance to push pixels around. You can pay Adobe $20/month for the privilege of launching Photoshop for just messing around (I hope not). You can use a web app and pray your browser doesn’t eat your work when you accidentally hit the back button (no hate to JSPaint, though….I love that).

Or you can just… not have a simple paint program, I guess.

I found this unacceptable. So I decided to build the tool I wanted. A bitmap editor that:

- Opens instantly

- Does exactly what you’d expect

- Looks like it belongs on a Mac

- Doesn’t require an internet connection, account, or subscription

- Uses less RAM than a single Chrome tab

I called it splatr.

Design Philosophy

Native or Nothing

I have a particular allergy to non-native software. Not because I’m some kind of purist—okay, maybe a little—but because I’ve experienced what software can feel like when it’s built for the platform it runs on. I know what native Mac software feels like, and I refuse to accept less.

splatr is built with Swift, SwiftUI, and AppKit. Zero dependencies. No CocoaPods, no SPM packages, no node_modules folder lurking in the shadows. Just Apple frameworks, talking directly to Apple hardware.

This matters. When you drag the brush across the canvas, you’re not waiting for a JavaScript event loop to notice. When you flood-fill an area, you’re not marshaling data across a web bridge. The code that handles your input is the code that draws your pixels. No translation layer. No abstraction tax.

The Floating Palette Problem

One of the earliest design decisions was how to handle tool palettes. The obvious SwiftUI approach would be to embed everything in the main window—a sidebar for tools, a bottom bar for colors. Clean, simple, modern.

But that’s not how paint programs work. Or rather, that’s not how paint programs should work.

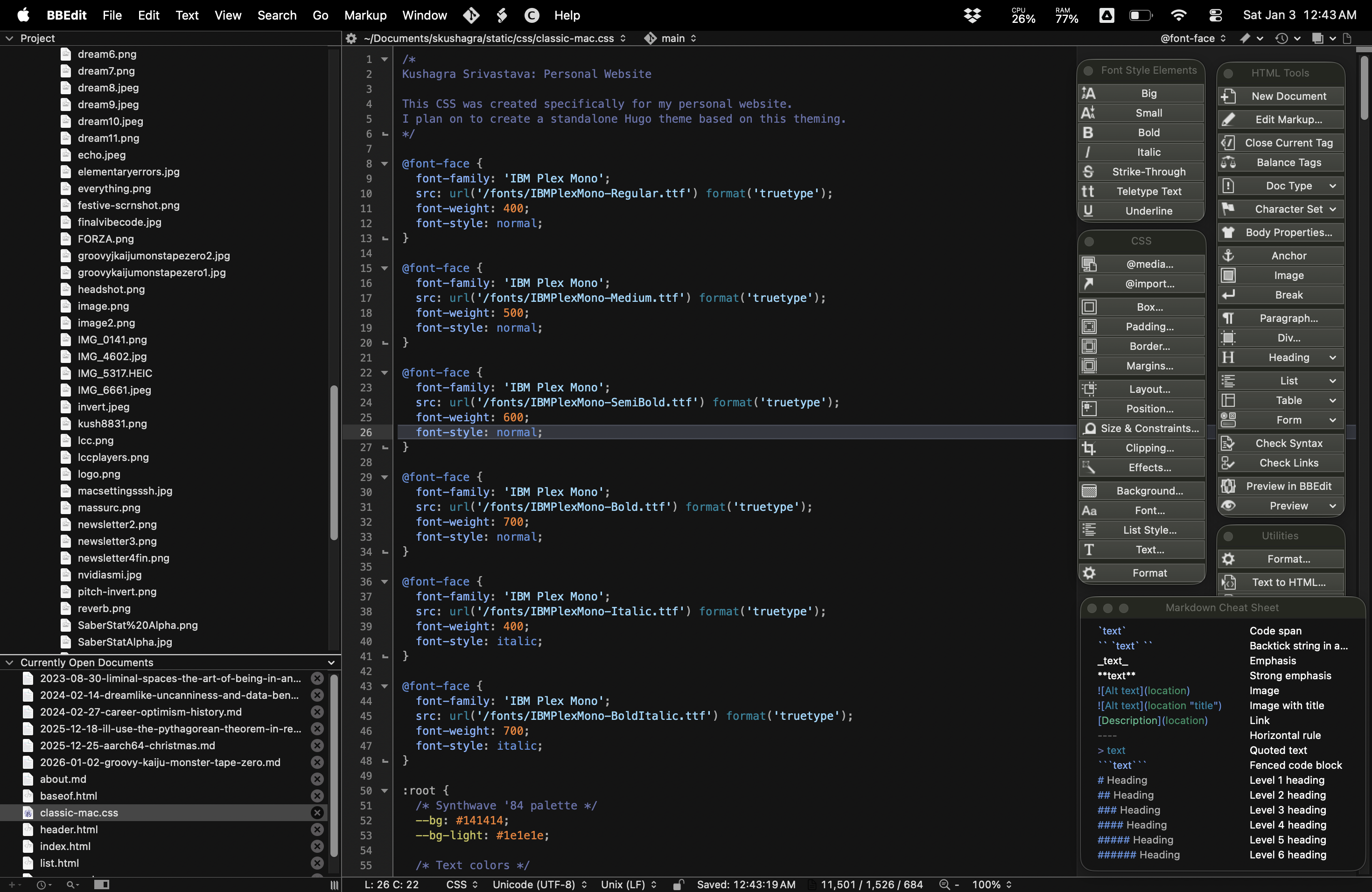

The floating palette paradigm exists for a reason: it lets you maximize canvas space while keeping tools accessible. You can shove the palettes into a corner, arrange them however you want, hide them when you need to focus. The canvas is the point; everything else should be subordinate to it. It’s what I love the most about my editor of choice: BBEdit.

So splatr uses NSPanel with the .utilityWindow style mask. These panels:

- Float above the main window

- Hide when you switch to another app

- Reappear when you switch back

- Work properly in full-screen mode

- Can be closed and reopened independently

This required dropping into AppKit for the panel management while keeping the panel contents in SwiftUI. A hybrid approach, but the right one. SwiftUI is great for building UI; AppKit is great for controlling window behavior. Use each where it’s strong.

The Tool Palette

The tool palette deliberately echoes the classic MS Paint layout: a 2×8 grid of tools, with contextual options appearing below based on the selected tool.

You can see all 16 tools at once, identify them by icon, and access any of them with a single click. Compare this to modern “ribbon” interfaces that hide tools behind tabs and dropdowns. The ribbon is better for discoverability in complex applications; the palette is better for efficiency in simple ones.

When you select a tool, the options panel below it changes contextually:

- Brush/Eraser: Size presets

- Shape tools: Fill style (outline, filled, filled with outline)

- Line/Curve: Width options

- Magnifier: Zoom level presets

Technical Deep-Dives

The Canvas Architecture

The canvas is an NSView wrapped in NSViewRepresentable for SwiftUI embedding. This was non-negotiable—SwiftUI’s Canvas view is great for vector graphics but lacks the low-level bitmap manipulation I needed.

The core rendering model is simple:

- An

NSImageholds the current canvas state - Drawing operations use

lockFocus()/unlockFocus()to draw into a new image - The new image replaces the old one

setNeedsDisplay()triggers a redraw

This is not the most efficient possible approach—you could maintain a CGContext and draw incrementally—but it’s simple, correct, and fast enough for bitmap editing at reasonable canvas sizes.

private func commitStroke() {

guard currentPath.count > 0, let image = canvasImage else { return }

let newImage = NSImage(size: canvasSize)

newImage.lockFocus()

image.draw(in: NSRect(origin: .zero, size: canvasSize))

// Draw the stroke

let path = NSBezierPath()

path.lineWidth = brushSize

path.lineCapStyle = .round

path.move(to: currentPath[0])

for point in currentPath.dropFirst() {

path.line(to: point)

}

currentColor.setStroke()

path.stroke()

newImage.unlockFocus()

canvasImage = newImage

saveToDocument()

}

The Flood Fill Incident

The first version of flood fill was a naive recursive algorithm. Click a pixel, check its color, fill it, recurse to neighbors. This works great for small areas.

For large areas, it ate my entire system. The app got quarantined by macOS for “excessive logging volume.” I saw the spinning beach ball of death. It was bad.

The problem was twofold:

- Using a

Set<String>for visited pixel tracking (O(n) string hashing for every pixel) - Calling

bitmap.colorAt(x:y:)for every single neighbor check

The fix was a proper scanline flood fill with a boolean array for visited tracking:

var visited = [Bool](repeating: false, count: width * height)

var stack: [(Int, Int)] = [(startX, startY)]

while !stack.isEmpty {

let (x, y) = stack.removeLast()

let idx = y * width + x

if visited[idx] { continue }

guard colorsMatch(bitmap.colorAt(x: x, y: y), targetColor) else { continue }

visited[idx] = true

bitmap.setColor(fillColor, atX: x, y: y)

stack.append((x + 1, y))

stack.append((x - 1, y))

stack.append((x, y + 1))

stack.append((x, y - 1))

}

Boolean array lookup is O(1). The fill is now instant, even on large canvases.

Coordinate System Hell

macOS has… opinions about coordinate systems. NSView traditionally has its origin at the bottom-left, with Y increasing upward. NSBitmapImageRep has its origin at the top-left, with Y increasing downward. SwiftUI uses yet another coordinate space.

Every tool that interacts with pixel data needs to account for this:

let bitmapY = Int(canvasSize.height - point.y)

I considered overriding isFlipped on the canvas view but decided against it—too many subtle interactions with the rest of the coordinate system. Explicit conversion at the boundaries is ugly but predictable.

The Document Model

splatr uses SwiftUI’s DocumentGroup scene with a custom FileDocument type. This gives you a lot for free:

- Open/Save/Save As dialogs

- Recent documents

- Dirty document tracking (the dot in the close button)

- Window restoration

The native format (.splatr) is dead simple: 16 bytes of header (width and height as Float64), followed by PNG data. This preserves canvas dimensions exactly while keeping the actual image data in a standard format.

if contentType == .splatr {

let width = data.withUnsafeBytes { $0.load(fromByteOffset: 0, as: Float64.self) }

let height = data.withUnsafeBytes { $0.load(fromByteOffset: 8, as: Float64.self) }

let imageData = data.dropFirst(16)

// ...

}

For export, we support PNG, JPEG, TIFF, BMP, GIF, and PDF. The PDF export creates an actual vector-ish PDF (well, a PDF with an embedded raster image at full resolution), which is useful for documentation.

What I Learned

SwiftUI Is Ready (Mostly)

SwiftUI in 2026 is genuinely good for building Mac apps. The declarative syntax is a pleasure, state management is sane, and the performance is fine for UI work.

But—and this is important—you still need AppKit for anything that involves serious window management or low-level drawing. The hybrid approach (SwiftUI for UI, AppKit for platform integration) is probably the right default for Mac apps that aren’t trivial.

Simple Software Is Hard

Making something simple is harder than making something complex. Every feature you add is a feature you have to maintain, document, and potentially break. splatr has exactly 16 tools because that’s how many a paint program needs. Not 15, not 17. Sixteen.

The temptation to add “just one more thing” is constant. Layer support? Selection transformations? Filters? All technically possible. All explicitly out of scope. splatr is a bitmap editor. It edits bitmaps. Scope discipline is a feature.

Native Software Is a Superpower

When your app is native, everything just works. Dark mode. Full screen. Keyboard shortcuts. Window management. Accessibility (mostly—still some work to do there). These aren’t features you implement; they’re features you get for free by building on the platform correctly.

This is the tax you pay for Electron: you get cross-platform deployment, but you lose platform integration. For some apps, that tradeoff makes sense. For a paint program that exists to be fast and simple, it’s unacceptable.

What’s Next

splatr is open source, MIT licensed, and available on GitHub. I’m calling it 1.0 because it does what I built it to do: edit bitmaps, simply and natively.

Future work might include:

- Undo/redo (currently limited—this is the big missing feature)

- Pressure sensitivity for tablet users

- A few more brush shapes

- Performance optimization for very large canvases

- Importing/Exporting Images

- Fonts/Text Resizing

- And way more features I am yet to implement

But honestly? It might stay exactly as it is. Software doesn’t have to grow forever. Sometimes done is a feature. I just wanted a proof of concept, and I am happy to deliver.

splatr is available now at github.com/suobset/splatr. It’s free, it’s open source, and it’s about 2MB.