Last week(ish), I spent about $40 (including shipping) on two Texas Instruments development boards: an MSP-EXP430FR4133, and an LP-MSPM0L1306 for general tinkering. Until now, I’ve mostly used Arduino boards for embedded projects. However, having some experience with TI’s toolchain from MITRE’s eCTF competition made me curious about trying something different.

Obvious disclaimer: Absolutely no details on the eCTF here, or anything. I just got exposed to these boards thanks to the competition, but I am buying these specific ones on my own for my personal projects; and just writing about why these have been a breath of fresh air.

This post isn’t about which platform is “better.” That’s a meaningless question without context. It’s about understanding what each platform does well, and why TI feels like a better fit for my current workflow, in general.

Why Arduino Matters

Before I get into TI, I want to be clear about something: Arduino is one of the most important developments in embedded systems education and hobbyist electronics. It’s not an exaggeration to say it democratized microcontroller development.

Before Arduino, getting started with embedded systems meant buying expensive programmers, learning vendor-specific IDEs, reading through hundreds of pages of datasheets just to blink an LED, and dealing with toolchain setup that could take days. Arduino collapsed all of that into “plug in USB, click upload.” That’s genuinely revolutionary.

The technical decisions Arduino made were smart:

- Abstracting the toolchain — You don’t need to know about avr-gcc, avr-libc, or linker scripts to get started. The IDE handles it.

- Consistent API across boards —

digitalWrite()works whether you’re on an Uno (ATmega328P), a Mega (ATmega2560), or a Due (ARM Cortex-M3). The abstraction layer means code is portable. - Integrated library manager — Need to talk to a sensor? Someone’s probably written a library.

#includeand go. - Serial as the universal debug interface —

Serial.println()isn’t sophisticated, but it works everywhere and requires zero setup.

The result is that millions of people who would never have touched a microcontroller are now building projects, learning electronics, and some of them are going on to become embedded systems engineers. That pipeline matters.

Arduino’s Technical Depth

There’s a misconception that Arduino is “just for beginners” or that it prevents you from doing real low-level work. That’s not true.

The ATmega328P on an Arduino Uno is a well-documented chip. You can absolutely work at the register level:

// Direct port manipulation on Arduino

// This is ~50x faster than digitalWrite()

DDRB |= (1 << PB5); // Set pin 13 as output (PB5 on ATmega328P)

PORTB |= (1 << PB5); // Set pin 13 HIGH

PORTB &= ~(1 << PB5); // Set pin 13 LOW

You can write inline assembly:

// Inline AVR assembly in Arduino

asm volatile (

"sbi %0, %1 \n\t"

:: "I" (_SFR_IO_ADDR(PORTB)), "I" (5)

);

You can use the avr-libc functions directly, access interrupt vectors, configure timers at the register level, and write pure assembly files that get linked with your sketch. The Arduino framework doesn’t prevent any of this — it just doesn’t require it for basic projects.

The arduino-cli gives you a proper command-line workflow:

$ arduino-cli compile --fqbn arduino:avr:uno MySketch

$ arduino-cli upload -p /dev/cu.usbmodem* --fqbn arduino:avr:uno MySketch

And PlatformIO in VS Code provides a professional development environment with proper autocomplete, project management, and even debugging support for boards that have debug interfaces.

The ecosystem is also genuinely impressive. Libraries for hundreds of sensors, displays, and communication protocols. Tutorials for almost any project you can imagine. Active forums where questions get answered. When you’re prototyping something new, that ecosystem can save you days.

Where TI Fit My Needs Better

So if Arduino is this capable, why did I end up spending $40 on TI boards?

Context matters. I’m currently competing in MITRE’s 2026 Embedded Capture the Flag (eCTF) — a semester-long embedded security competition where teams design secure systems on real hardware and then attack each other’s implementations. This year’s competition uses the Texas Instruments MSPM0L2228 platform, a Cortex-M0+ board with 256KB flash and 32KB SRAM.

So I’ve been deep in TI’s toolchain for the past couple of weeks. The boards I bought are partly to have hardware around for personal projects, and partly because I’ve already climbed/am climbing the learning curve for this ecosystem.

But beyond just familiarity, there are specific features that matter for my current work:

Built-In Debug Probe

TI LaunchPads have an XDS110 debug probe built into the board. Plug in USB, and you have full JTAG/SWD access. No external hardware, no modifications, no special setup.

$ mspdebug tilib

(mspdebug) prog main.elf

(mspdebug) break main

(mspdebug) run

You can set breakpoints, inspect memory, single-step through instructions, set watchpoints, and connect GDB — all out of the box.

Arduino boards can do GDB debugging, but it requires either a software GDB stub (which consumes resources and your UART) or external hardware like an Atmel-ICE plus fuse modification. It’s doable, but it’s not the path of least resistance.

(NOTE: Some Arduino-compatible boards, like certain SAMD21 or ESP32 boards, have built-in debug probes. But the standard Arduino Uno or Mega do not.)

EnergyTrace Power Profiling

TI’s EnergyTrace is integrated into the debug probe and lets you profile power consumption in real-time — down to 5nA resolution, correlated with code execution, showing peripheral states and CPU low-power modes.

This has no Arduino equivalent. On Arduino, power profiling means external hardware (multimeter, oscilloscope, Nordic Power Profiler Kit) and manual correlation with your code.

(EnergyTrace is specific to certain TI parts and their debug probes, so it’s not universal across all TI boards. But for the LaunchPads that support it, it’s a powerful feature.)

For battery-powered applications or ultra-low-power design, EnergyTrace is a significant advantage. For most hobby projects, it’s overkill.

FRAM on Specific Parts

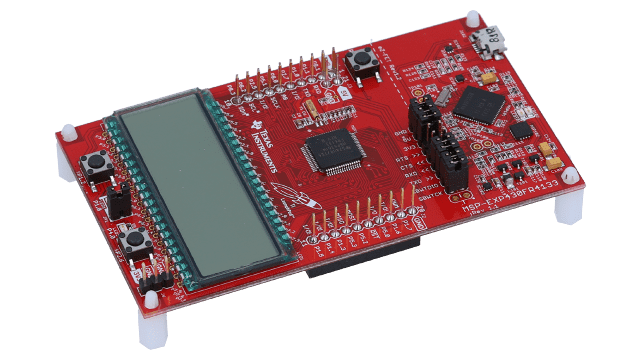

The MSP430FR4133 I bought uses FRAM instead of Flash — 10^15 write endurance vs 10^5, with much faster writes and no erase cycles required. This is specific to certain TI parts and has no Arduino equivalent.

For a data logger that writes frequently, FRAM matters. For most projects, Flash endurance is fine.

The Unix Workflow

One thing I appreciate about TI’s toolchain is how well it composes with standard Unix tools. The board appears as a standard serial device:

$ ls /dev/cu.usbmodem*

/dev/cu.usbmodem14301

(NOTE: Arduino boards also appear as serial devices, so this isn’t unique to TI.)

Flashing and debugging are command-line operations that can go in a Makefile:

PORT := $(shell ls /dev/cu.usbmodem* | head -1)

flash: firmware.elf

mspdebug tilib "prog $<"

debug: firmware.elf

mspdebug tilib "gdb" &

sleep 1

arm-none-eabi-gdb -ex "target remote :2000" $<

But Arduino has this too now. The arduino-cli and PlatformIO both support command-line workflows. This isn’t a TI-specific advantage anymore.

However, arduino-cli can be clunky for complex projects — TI’s toolchain feels more straightforward for multi-file C projects with custom linker scripts and startup code. Less fighting with the build system when you want to do something non-standard. Arduino can use Makefiles or CMake, but it’s not the default path, and you end up working against the grain. Coming from x86 assembly and systems programming, TI’s approach just feels more familiar: arm-none-eabi-gcc, mspdebug, standard Makefiles, direct register manipulation. Arduino’s abstractions are great for beginners, but they can get in the way when you want to dig deeper.

Choosing Based on Context

Here’s how I’d actually think about platform choice:

Arduino is probably the right choice if:

- You’re learning embedded development

- You’re prototyping and need fast iteration

- You need a specific library that exists in the Arduino ecosystem

- You’re working with others who know Arduino

- You don’t need real-time power profiling

- Standard Flash endurance is sufficient

TI (or similar vendor-specific toolchains) might be better if:

- You’re doing power optimization and need EnergyTrace-level profiling

- You need specific hardware features (FRAM, specific peripherals)

- You’re already invested in the ecosystem for another project

- You’re doing security work where memory inspection matters

- You want to learn a more “traditional” embedded workflow

Neither list is about capability — Arduino can do debugging with the right setup, and TI boards can be used for rapid prototyping. It’s about what the platform makes easy by default.

What I’m Actually Building

The honest answer is: I don’t know yet. I have enough projects between eCTF, coursework, and research projects. The boards are for having hardware around when inspiration strikes.

Maybe something with the FRAM. Maybe I’ll play with the segmented LCD on the FR4133. Maybe I’ll just blink LEDs and appreciate that I can set a hardware breakpoint while doing it.

I’ll probably update soon on this front.